Continued from Part One published on May 16, 2018.

The skeletal beauty

“Victory sank on the captain’s second voyage to the Maldives,” said Saeed. “On his first journey, the captain miscalculated the distance to Male and ended up all the way in Vaavu Atoll. Then on his second journey…” he trailed off with a wry laugh.

Though Victory met a watery death on the unfortunate captain’s second trip, the expensive goods she was carrying were not beyond saving. A team was put together which, led by Hassan “Lakudiboa” Manik, began the operation to salvage the wreck’s cargo.

“The cars were the first things we salvaged,” he had said in an interview to veteran diver Adam Ashraf. The recovered goods were later auctioned off.

Amongst those who got to see the salvage process was Hussain “Sendi” Rasheed, a renowned name in the Maldivian diving industry.

“My first dive was at the Victory wreck,” revealed Sendi, who had regularly visited the site between 1981 and 2003.

Over the course of 20 years, Sendi was able to observe MV Victory’s metamorphosis from lifeless skeleton to a vibrant ecosystem pulsing with life. Lying upright and parallel to Hulhule’s reef, she naturally became a breeding ground for corals; and the multitude of marine life she attracted, along with great visibility due to the currents in that area, established Victory as one of the hottest dive spots in the Maldives.

“This is one of the most beautiful wrecks, and one of the biggest. It’s around 110 metres in length,” stated Sendi.

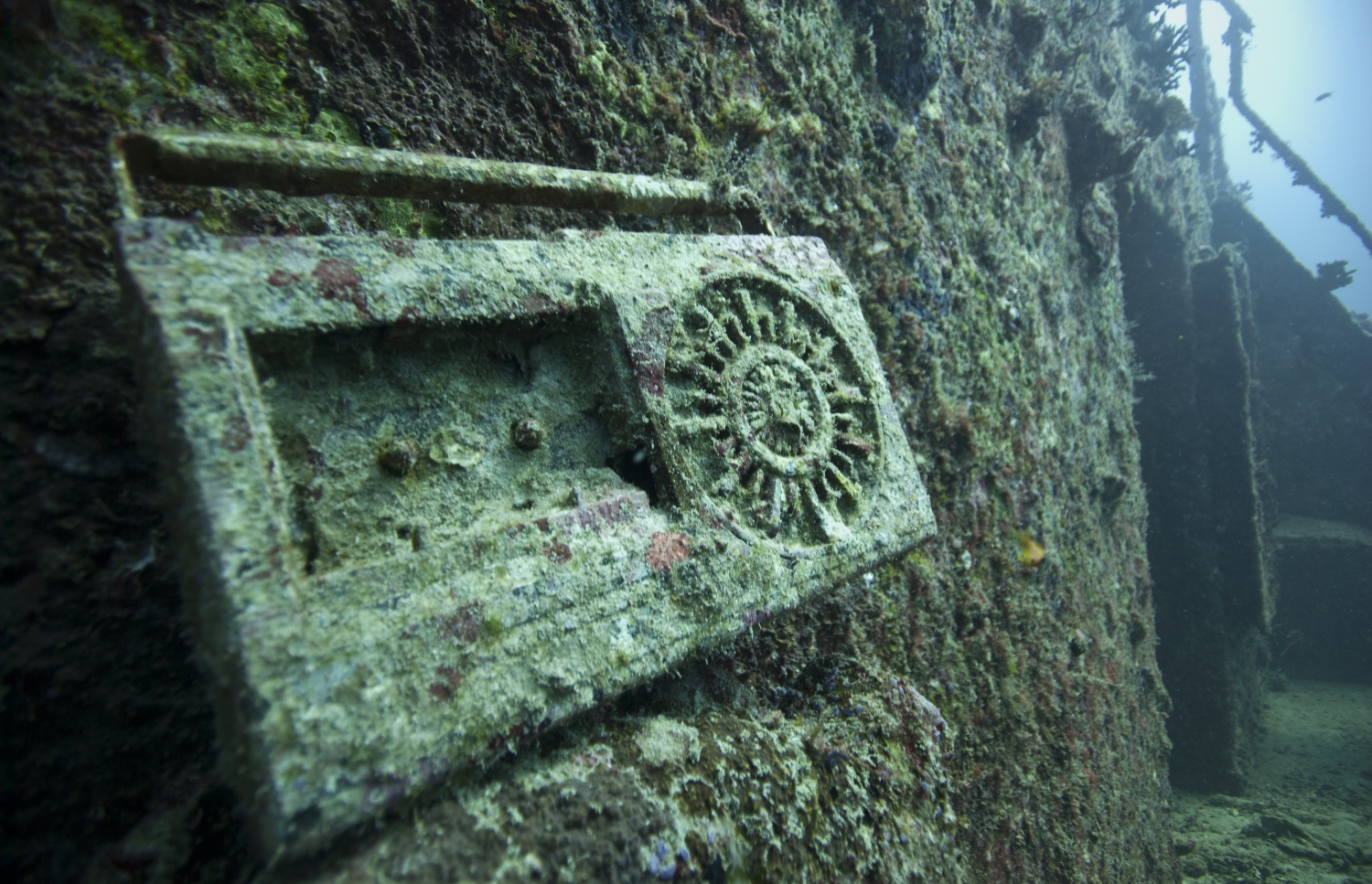

However, even 37 metres underwater, Victory did not lie undisturbed for long. Bits and pieces began to disappear. Portholes, doors, the anchor and steering wheel fell prey to scavengers until all that remained by the year 2000 was “a metal skeleton”.

The culprits behind the robberies included local and tourist divers – a foreigner had personally shown Sendi one of Victory’s portholes, wrapped up and ready to be shipped to her home country as a souvenir.

“Everything that could be physically removed was gone … It’s like breaking into a museum,” said Sendi, expressing frustration over the lack of established laws and regulations to ensure the protection of shipwrecks.

Though the rich coral life and abundant fish surrounding MV Victory remained ever picturesque, Sendi noted with remorse that her true beauty remained lost to those viewing her after the new millennium.

Onslaught of damages

Victory, and by extension the diving sector, suffered more blows years later when the site was closed down in March 2016 for the development of the China-Maldives Friendship Bridge between Male and Hulhule. The bridge is a mere 500 metres away from Victory’s resting place.

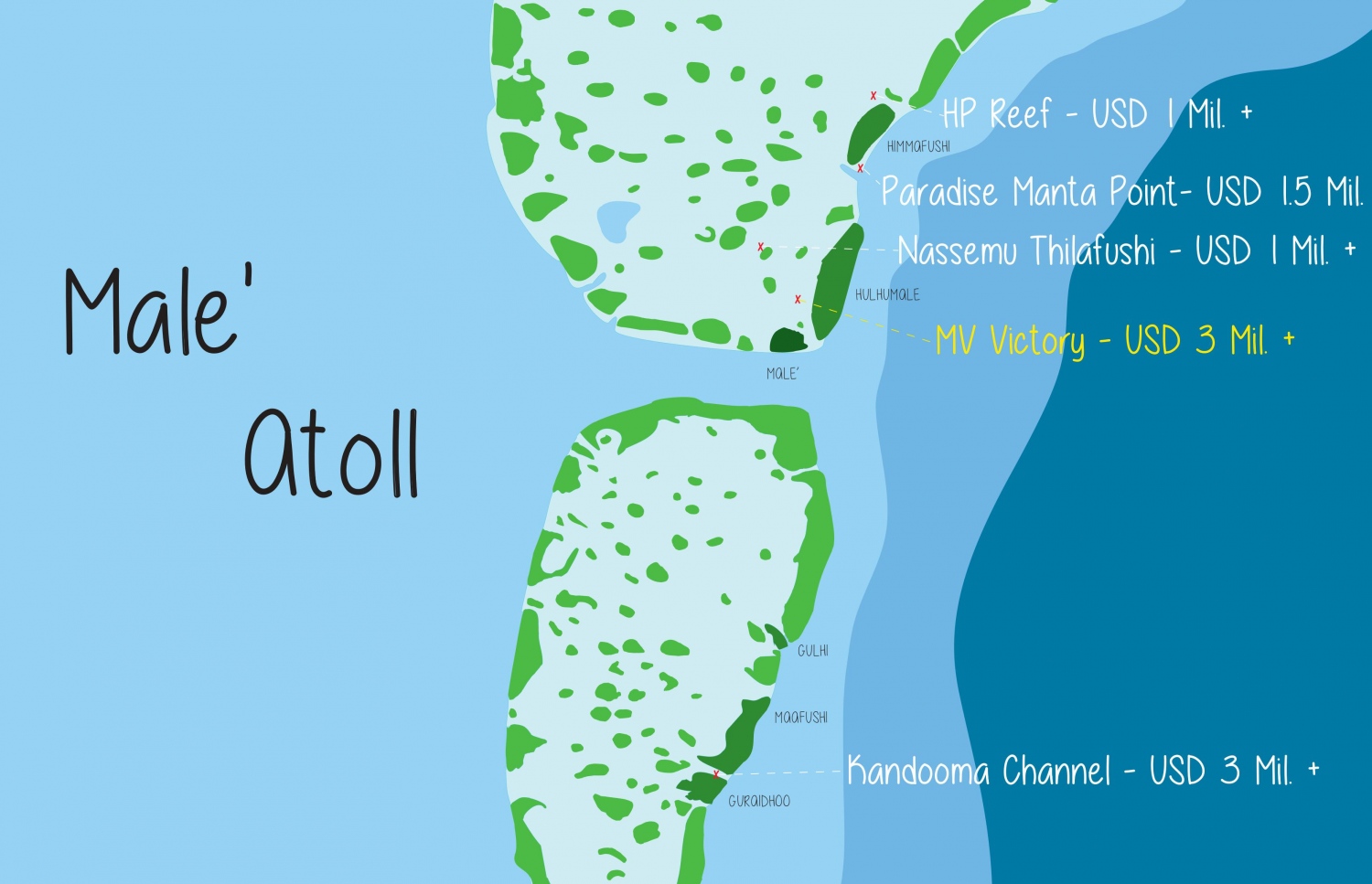

The first setback was the abrupt cessation of revenue. Wreck diving, though a rather obscure activity for most civilians, holds a significant popularity for divers who travel to the Maldives from around the world. As such, MV Victory was responsible for contributing to the attraction of hoards of visitors daily from within the central atoll dive circuit.

According to Sendi, local dive guides typically escorted a minimum of eight dive boats, with around 15 divers on each, to Victory every day.

“That’s an income of at least USD 3 million from Victory alone, every year,” said Sendi.

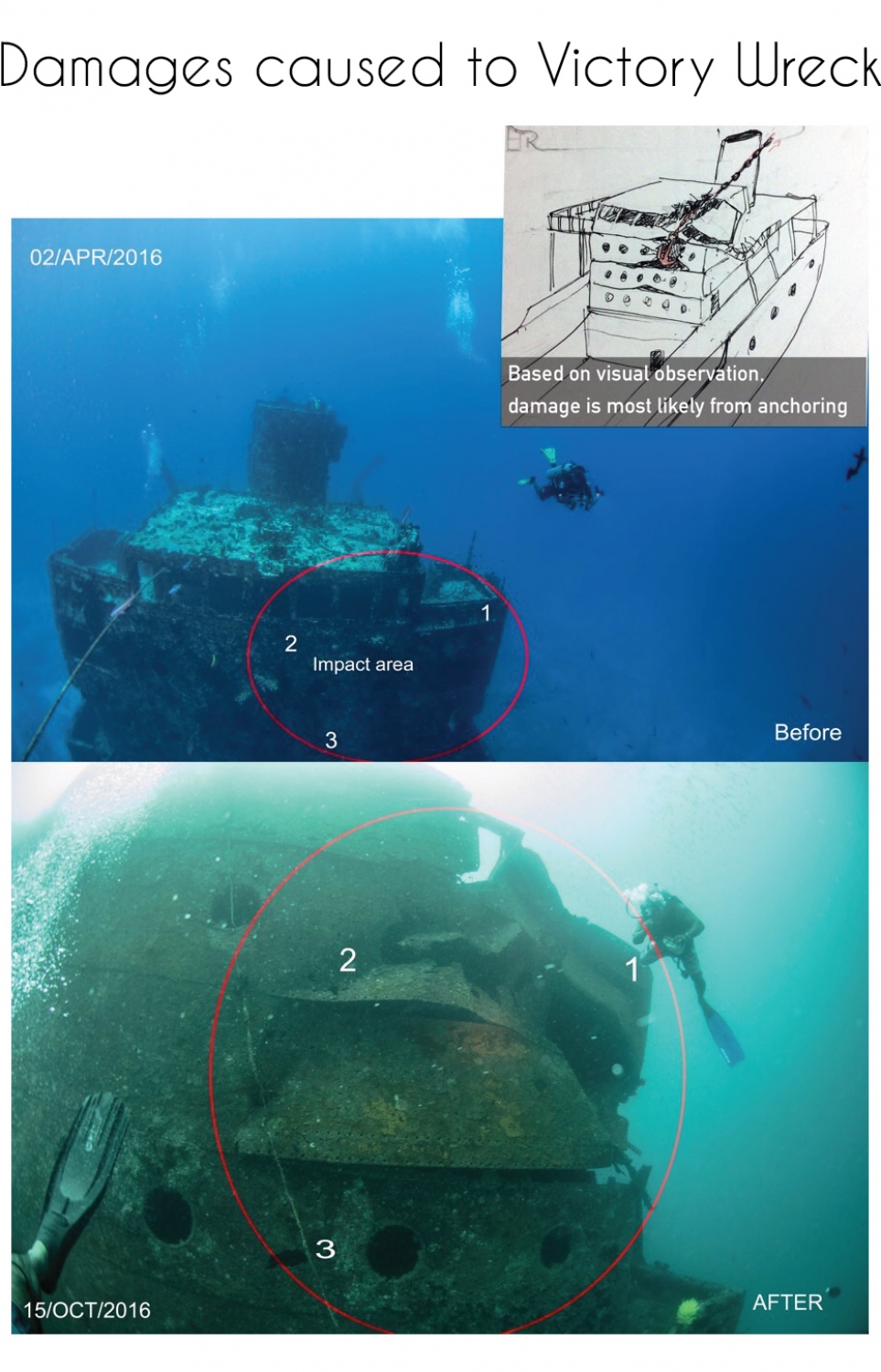

The second blow to MV Victory did not take place till later that year when Dive Instructor Adam Ashraf, having extensively researched the wreckage for years, approached the government regarding protecting the wreck during the construction and development of the bridge. He led a team of divers to set up four buoys to mark Victory’s location so that bridge workers would steer clear of the wreck site.

However, later it was discovered that Victory had sustained damages of magnitudes that could only be caused by dropping anchors of vessels, which were deployed around the bridge, onto the wreck. With the housing ministry’s permission, a team of divers inspected and documented the damages: two wings of Victory’s wheelhouse had been destroyed, while several cabins on one side, including the captain’s, were crushed.

Subsequently, Ashraf proceeded to meet with the boat captains working around the bridge, intending to expand their awareness on MV Victory's importance. However, her proximity to the bridge meant other adverse effects continued; the ongoing construction work disrupted the ocean floor, encasing the wreck in the suspended sediments, thus suffocating the corals and chasing marine life away from their homes.

Heaving a sigh, Sendi recalled his last dive to Victory, accompanied by Ashraf: “There’s no more life now.”

“Shipwrecks are underwater museums”

Though Sendi and Ashraf remained optimistic that coral and other marine life would return to Victory once the bridge has been completed, both admitted that all the damages might not be repairable – damages that could have been prevented had there been proper protocols.

“We need to regulate diving, or establish standards and regulations for wreck diving,” said Sendi.

The divers stressed that it was imperative for authorities to protect shipwrecks for the sake of heritage and tourism promotion. Though all sunken vessels become state property under Maldivian law, they claimed that proper steps have not been taken to preserve them.

“[Victory] belongs to the museum. It should be an asset of the museum,” Sendi declared, stating that all shipwrecks in Maldivian waters should fall under the ownership of the National Museum.

Describing them as underwater heritage sites, Sendi said that under the museum’s protection, shipwrecks could be properly maintained and conserved for future generations.

He added that preserved shipwreck sites could possibly generate sustainable revenue towards the maintenance of these sites by providing additional income serving the needs of the hospitality sector.

“Wreck sites could be sold as facilities for wreck diving training,” said Sendi. “… The museum could also charge fees for divers to visit wrecks.”

It is the divers’ long-enduring wish to see a day when the shipwrecks, scattered across the atolls, would be properly protected and conserved. Listing some of his favourite sites such as the wrecks at Fesdhoo, Halaveli, and Macchafushi, Sendi added, “Every individual wreck has a story” – such as the tanker “British Loyalty”, which was torpedoed by the German navy in 1944 and later scuttled by British forces off the coast of Addu Atoll’s Hithadhoo in 1946; a unique relic of the Second World War that is now another top dive site in the Maldives.

“Underwater archaeology, museums, history – shipwrecks are symbols that represent all of these.”